On this blog, we’ve been working through all seven key expense areas, and we will cover equipment costs for optometry practices this week. Equipment costs are complicated. First, let’s look at the typical P&L expenditures on equipment, followed by some balance sheet assets and liabilities 101. If you’ve been waiting for a real-world discussion of why cash flow and profitability aren’t the same, this blog is for you.

How Much Equipment Costs Show Up On a P&L?

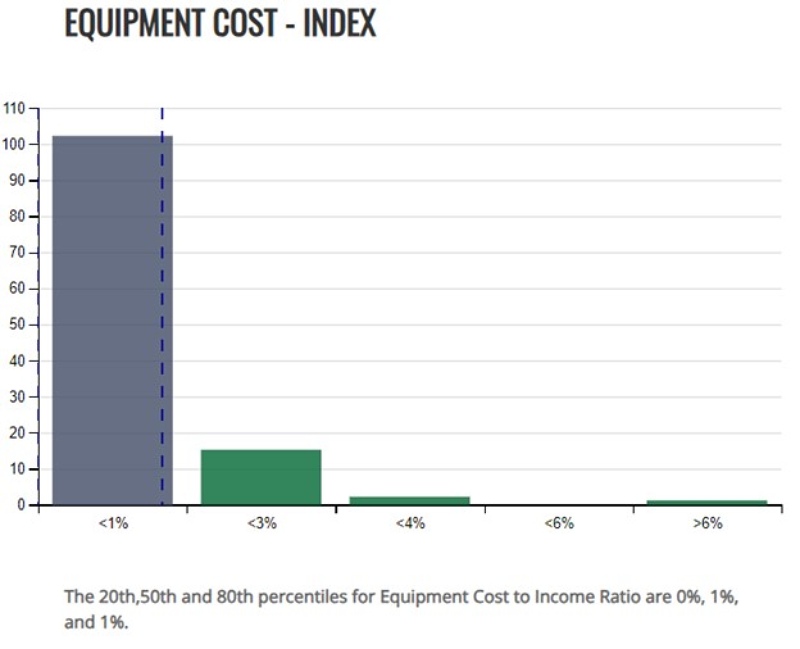

The chart below shows equipment expenses as a percentage of total revenue on P&Ls for over 100 Books & Benchmarks clients:

This includes leases, maintenance contracts, and equipment purchases under $2,500, which is the typical IRS threshold for capitalizing asset purchases (assets are things a business owns; capitalizing means they’re put on the Balance Sheet instead of expensed on the P&L).

To make matters even more confusing, not all leases are like leasing a car, where you know you’ll have to return it after three years or so. Many equipment leases are “capital leases,” which is another way of structuring a loan. And these also go on the balance sheet, not the P&L.

Why Can’t I Expense My Equipment Purchases?

Most practices want to put new equipment on the P&L so they can deduct the expense for tax purposes. A tax deduction is great, but remember, financial statements should do more than support tax returns.

Because most assets will last longer than one year, it can be deceptive to book their full cost in just one year. If you expect your new OCT to last eight years, planning for the next one can be hard if it looks like your current OCT costs nothing for the seven years leading up to the replacement.

Many businesses keep a set of books that amortizes the cost of assets on the P&L over a period of years. For example, an $80,000 wide-field camera with an eight-year life expectancy might be depreciated on the P&L at $10,000 per year to reflect an “annual” cost of the asset. This is especially common for large companies with asset purchases well above the tax code’s Section 179 limits on accelerated depreciation.

But that’s just context. The practices we work with are too small to have a business set of books separate from the financials they use for taxes. And hardly any of them have exceeded their ability to fully depreciate their equipment purchases the year they buy them. (By the way, whether you should fully expense depreciation or spread it out over several years is a great conversation to have with your CPA.)

TLDR: If My Equipment Isn’t on My P&L, Where Does It Show Up?

When you buy an asset that’s capitalized (again, we capitalize any single asset bought for over $2,500; four $700 computers with a $2,800 invoice still show up on the P&L), several things will happen, especially if you finance the purchase with a loan.

- When you take out a loan, the loan balance shows up on the liability portion of your P&L. The principal that will be paid back within 12 months is a Current Liability, while the remaining loan balance falls under Long-Term Liabilities. And your Cash briefly increases by the loan amount.

- After you buy the equipment, cash decreases by the equipment cost, and the assets portion of your Balance Sheet goes up by the value of the equipment.

- Once you take depreciation, the depreciation shows up on the P&L as an Expense and on the Balance Sheet as Accumulated Depreciation.

- When you make your monthly loan payments, your cash decreases with each payment. The principal portion of the payment reduces the loan liability on the balance sheet. The interest, which is the cost of borrowing money, is deducted on the P&L.

Profit and Cash Flow Aren’t the Same Thing, Especially When Debt Is Involved

It’s important to note that the only cash expenditure you’ll see on your P&L from repaying loans is the interest. Depreciation is a non-cash expense. So, if you have a loan you’re paying back, the Net Income amount at the bottom of your P&L is not the same as the cash available for distributions.

(You probably know this already, but even if you’re debt-free, you still need to plan for taxes and ensure the practice has ample cash for its own reserves before taking distributions. But that’s a topic for another blog.)

If you’re worried about cash flow in your practice—especially if you’re about to expand and you’ll be using debt to fund your expansion—having an accurate Balance Sheet is critical to tracking where your cash is going.

Most of the time, your balance sheet doesn’t matter. Until it does. And when you’re in a tough spot, fixing balance sheets is not easy or quick.

If you want to be sure that you’re accounting for your loans and assets correctly, contact us today and find out how our professional optometry bookkeeping team can make sure your financials are always accurate, meaningful, and up to date when you need them. You’ll sleep easier at night, and as a bonus, planning for taxes and deciding on the right distributions to take will be easier too.